| DOUG KINSEY – October 21, 2012|By ANDREW S. HUGHES | South Bend Tribune |

Doug Kinsey has a favorite analogy that perhaps explains why he gravitates toward social justice issues in his painting. The comparison boils down to the difference between light conversation at a party and a serious discussion with a friend facing a significant problem. “Suddenly everything seems real,” he says about the latter form of conversation. “Some people call that depressing, but I think it’s being hooked into real life. … There’s bound to be sickness and discomfort and war. It just seems inevitable that it’s part of the fabric of life, and to deny that is being superficial.” A professor emeritus of art at the University of Notre Dame, Kinsey’s devoted the vast majority of his career to issues of social justice, and, as with his past exhibitions, the paintings currently on display at the South Bend Museum of Art in “The Displaced” are anything but superficial. The people in the paintings are all refugees, chased from their homes by war, natural disasters, and poverty. But the paintings themselves aren’t depressing. They’re resilient, instead.

In the brightly colored “Rest Stop,” for example, the expression of affection between what appears to be a mother and her son is nearly Rockwellian in its unabashed sentimentality. Subject unites the works in “The Displaced,” but so does Kinsey’s approach to it. Each work features multiple characters, most of them in close proximity to each other, often touching, their bodies sometimes even blending into a single form: Misery and strife may be part of their lives, but these people aren’t alone. “I think there’s a certain kind of optimism about this,” he says, “that belonging to a community is very helpful for survival. … I think there’s a real value for community and for community to make it possible to put up with catastrophe.” And the catastrophes are real: All of the works in “The Displaced” and an ongoing exhibit at the LaSalle Grill of his dance paintings began as photographs Kinsey clipped from newspapers, mostly The New York Times.

But despite his use of news photographs as a means to have an objective starting point for what is ultimately a highly subjective process, Kinsey thrives on ambiguity in his work — nationalities, settings and even actions often are purposely blurred. The family gathered around a campsite in “Open Kitchen Diptych,” for instance, could just as easily be Steinbeck’s Joads on the road to California as it is a Korean family displaced by an earthquake — Kinsey’s photographic source for the painting. “But that’s really part of my rationale for using so many different cultures,” he says, “that it’s all part of the same thing. … These came from specific pieces of history, and yet I want these to fit into the lives of the people looking at the paintings. If you get too specific, you can exclude people. I think what’s being shown in these paintings has relevance to a lot of people, but it works better if they’re open and not too specific.”

PAINTING AND TEACHING

In addition to the SBMA and LaSalle Grill exhibits this fall, Kinsey also will receive the museum’s 2012 Carlotta Banta Award for Artistic Achievement at its “Beaux Arts Ball: Encore! Encore!” fundraiser on Nov. 10 at Century Center (June H. Edwards will receive the Banta Award for Friend of the Arts). The honor gratifies him, but he also downplays it as proof that he’s lived in South Bend “a long time” and is “old.” Born in Oberlin, Ohio, in 1934, Kinsey graduated from Oberlin College and earned his master’s in fine art from the University of Minnesota. He joined Notre Dame’s art faculty in 1968 and taught there for 31 years while also producing more than 70 solo exhibits in the U.S. and in such other countries as England, Sweden and Japan. Kinsey also has illustrated more than 15 books and has taught at the University of North Dakota, Berea College, Oberlin and Japan’s Kobe College. “I have quite a bit of contact with a number of students, particularly the ones who are still painters and making their living with something to do with painting,” he says and adds that more than a dozen former students have returned to South Bend to view “The Displaced.” “Teaching’s very exciting,” he says. “You’re with people who are at an age when they’re flexible and trying to develop themselves, so it’s a very personal thing and very exciting.” Retirement, however, has provided Kinsey with the opportunity to paint more and work more on his technique. He’s learned how to draw better, he says, and he has more experience with paint and different ways to apply it to the canvas, as well as how to compose the images.

He included 1995’s “Open Kitchen Diptych” in “The Displaced,” the show’s oldest painting by a wide margin, to illustrate how his technique has changed over the last two decades. “It’s the same person,” he says, “but the form changes.”

OBJECTS THATARE MADE

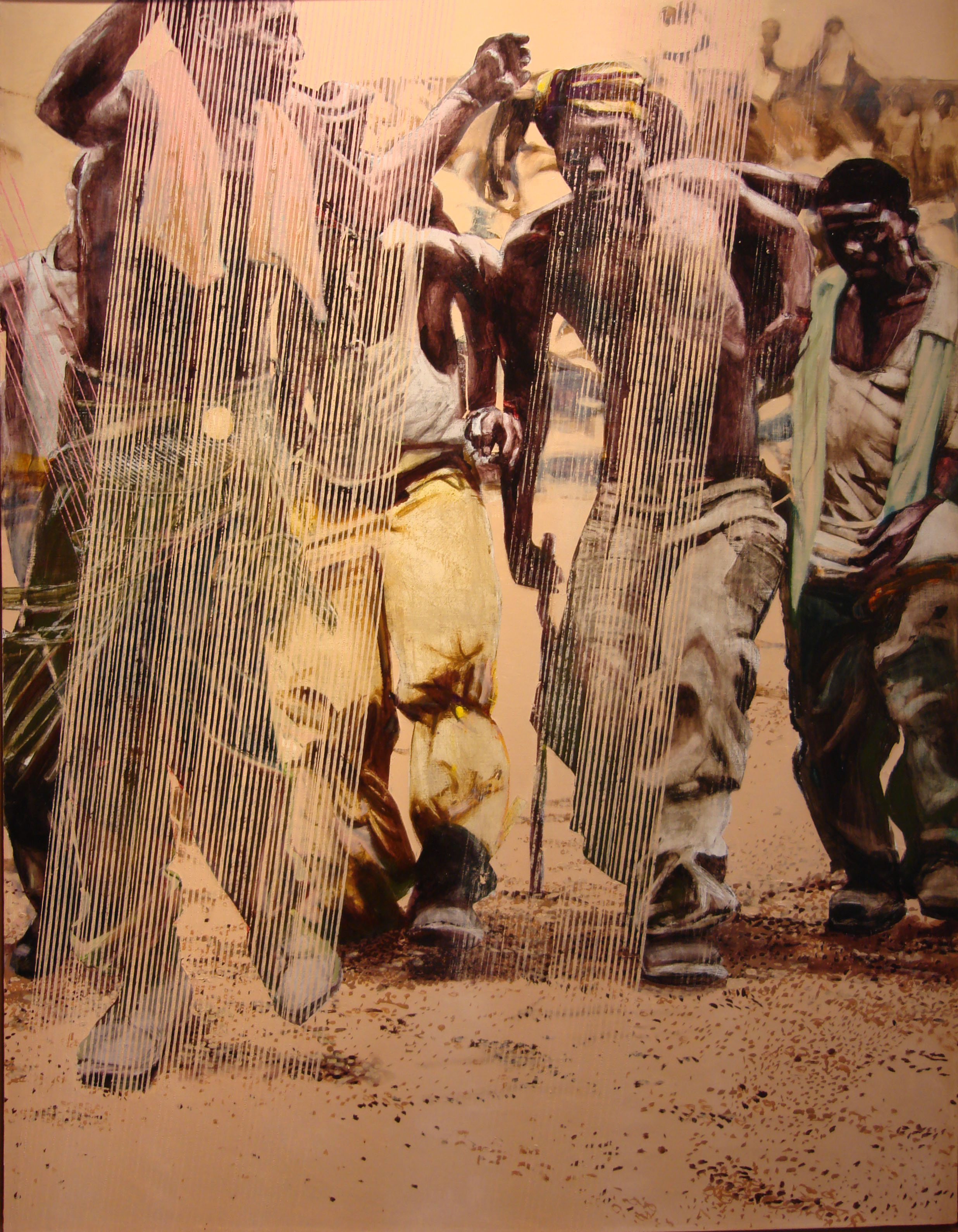

Technique and process matter to Kinsey. “Every painting is two things,” he says. “One is an illusion of space. It might be highly realistic or abstract, but it’s going back and fooling a person into thinking he’s looking onto a window into something. Two, it’s an object that was made. … I think a very important part of the experience of a painting has to do with how it was made and revealing to the observer how it was made. This really leads the viewer to a certain temperament a painting has.” As an example, Kinsey points to “Son of Man,” a painting of a boy sitting in the middle of sleeping figures that came from a photograph of a refugee camp in a high school in Holland during World War II. “It was painted in a very lively manner,” he says. “It’s not a painstakingly detailed painting that’s tight. It’s very loose and expressive, relaxed. It was driven, but in a very emotional style. … That is something that’s very different from tight and photographic, which is technique I love, but I think is detached.” With most of the paintings in “The Displaced,” Kinsey added extra layers of paint in the form of designs from stencils and the use of vertical and diagonal lines applied on top of the main image. In “The Long Wait,” Kinsey used stencils to create the pattern on the dress of the woman in the front of a line of two or more dozen people, making her the focal point of interest. But he added the vertical lines at center after he finished the painting because it “looked like a run-on sentence” and he wanted to give the viewer two separate zones of interest. Similarly, Kinsey created 2003’s “Flight” from a photograph of the U.S. bombing Baghdad, with hundreds of people running toward the viewer, four of them in the foreground under the haze of greenish-yellow lines. “Halfway through painting, I realized half of the people in it were having a different experience,” he says. “The ones under the lines were bent over. I think they were being shot at. … I sensed two different states, so I emphasized it with the lines.” Kinsey borrowed the idea for the lines from a woodcut of travelers in the rain by the 19th-century Japanese print artist Hiroshige. He saw them as a metaphor for “the slings and arrows of life,” but he’s also uses the layered vertical and diagonal lines to suggest different worlds, to separate people and, mostly, to add energy. In “Border Crossing II,” for example, crisscrossed diagonal lines imply hurried movement, but they also create tension by suggesting different directions — and outcomes — the two figures in the painting could take. “It’s decorative and exciting,” he says about the lines in general, “but I think it also causes anxiety, and I don’t trust any art that doesn’t cause anxiety.”

|